Home » Lifespan Faith Development » Tools for the Journey

Tools for the Journey

Insight, Inspiration, and Resources for Daily Life

- Set Boundaries, Find Peaceby Meredith Plummer

Picture by Pexel contributor RDNE Stock Project Kindness is Not Weakness

In recent years I’ve taken on the task of reconnecting with childhood friends. In our conversations, there is one common refrain I’ve heard over and over again. These old friends seem compelled to tell me how I was always ‘so kind,’ or in some instances ‘the nicest person they knew.’ Which, strangely enough, kind of makes me sad. For starters, how sad that I was the nicest person they knew throughout their childhood. And, second, some have been inclined to see my kindness as weakness. All of which got me thinking, maybe I need to do some work around boundaries. So, I choose Set Boundaries, Find Peace by Nedra Glover Tawwab as one of my sabbatical reads. But, now, 9 months later, I am not sure if this is the book I really needed. My kindness is not a weakness, nor does it stem from a lack of boundaries. However, just because this book wasn’t for me, doesn’t mean it isn’t for you. So, here are the quotes and questions I have gathered…

Quotes

- It’s not my job to save people. It’s not my job to fix people. I can help people, but I can’t fix them. p. xvii

- This reflects the number one reason that people avoid setting boundaries: fear of someone getting mad at them. p. xvii

- Boundaries are expectations and needs that help you feel safe and comfortable in your relationships. p. 5

- If you think about it, the root of self-care is setting boundaries: it’s saying no to something in order to say yest to your own emotional, physical, and mental well-being. p. 6

- When we’re resentful, we do things out of obligation to others instead of for the joy of helping. p. 6

- Boundaries are essential at all ages. They change in relationships, just as the people in relationships change. Transitions… often require new ones. p. 9

- Healthy boundaries… require an awareness of your emotional, mental, and physical capacities, combined with clear communication. p. 12

- In a recent Instagram poll, I asked “When you’re having an issue, what would you prefer? A: Advice or B:Listening?” More than 70 percent of the 4,000 people who answered said, “B: Listening.” It seems that most of us just want to be heard. A fundamental boundary is learning to listen without offering advice. p. 122

- Real acts of self-care have little to do with spending money. Instead, they’re about showing up for yourself by setting boundaries. p. 154

- In most marriages, people report a decline in satisfaction during the first year, soon after kids are born, and when the kids leave home. p. 200

- Having kids isn’t a reason to abandon yourself and your marriage. p. 202

Questions

- How are you at setting and keeping boundaries?

- Are there certain areas in your life that could benefit from a re-evaluation of your boundaries?

- How are you at accepting other’s boundaries?

That’s it for this month. I hope you will join me next month, as we explore a work I am still wrapping my head around, How we Show Up by Mia Birdsong. Thanks!

- How to Keep House While Drowningby Meredith Plummer

I Am Drowning, there is No Sign of Land.

From Matt Hardy on Pexels Have you ever heard “No Children” by The Mountain Goats? It was popular on Tiktok a few years back. If you were on Tiktok during the Pandemic you probably remember those videos. You probably also remember K.C. Davis who made a name for herself as a compassionate, neurodiversity affirming therapist. When her book, “How to Keep House while Drowning,” came out, I just knew I had to read it. And, I am so glad I did. In her book, Davis not only provides neurodivergent-positive strategies for basic care tasks (e.g. cleaning, bathing, exercising, etc.) but also a functional framework for care tasks that is deeply grounded in self-love and grace. In all honesty, the only gripe I have with this book is that it wasn’t available during the pandemic, when I was drowning. Here are the quotes and questions I gleamed from it…

Quotes

- Like a snake, I felt the voice that visited me nightly crawl up my thought, wrap its body around my neck, and hiss into my hear, “See? I told you you were failing.” My professional experience as a therapist had shown me time and time again that being overwhelmed is not a personal failure, but as most of you may know, the gulf between what we know in our minds and what we feel in our hearts is often an insurmountable distance. p. 3

- In fact, I do not think laziness exists. You know what does exist? Executive dysfunction, procrastination, feeling overwhelmed, perfectionism, trauma, amotivation, chronic pain, energy fatigue, depression, lack of skills, lack of support, and differing priorities. p. 5

- When barriers to functioning make completing care tasks difficult, a person can experience an immense amount of shame. p. 6

- You are already worthy of love and belonging. p. 9

- Care tasks are morally neutral. Being good or bad at them has nothing to do with being a good person, parent, man, woman, spouse, friend. Literally nothing. p. 11

- [Fill in the blank] “It would be such a kindness to future me if I were to get up right now and do ___” p. 13

- Think of what you would say to a friend who was struggling and turn the message inward. p. 36

- Anything worth doing is worth doing partially. p. 47

- I find this stems from that binary view of care tasks that they can be only either done or not done and that done is the superior state. But keeping everything done isn’t the point. Keeping things functional is the point. p. 51

- If you never figure it out but have less shame in your life and more joy, I’d say that’s a win. p. 64

- You are not responsible for saving the world if you are struggling to save yourself. If you must use paper plates for meals or throw away recycling in order to gain better functioning, you should do so. p. 65

- No person can do all the good things all the time and expecting yourself to just sets up an oppressive perfectionism to which no one can live up. Imperfection is required for a good life. p. 66

- Those who work in shame also rest in shame. Instead of relief, taking a break only brings feelings of guilt. p. 91

- The balance between rest and work seems to work itself out pretty naturally when you practice self-kindness. p. 94

- There are seasons of life when we just can’t get all of our needs met, but the mental shift of seeing rest not as a luxury but as a valid need helps you get creative, or at least validates it’s okay to mourn how difficult life is right now. p. 95

- [Speaking about partnerships] The should not be to make the work equal but to ensure that the rest is fair. p. 97

- Move as slowly as you need to. p. 107

- The best way to do something is the way it gets done. p. 118

- Creating momentum is key because motivation builds motivation. p. 120

- Self-care was never meant to be a replacement for community care. p. 131

- When did movement lose its pleasure? When did my adult life stop including activities that made movement joyful? Can I get it back? Can you? Can we try together? p. 137

- There are no good or bad foods. There are no right or wrong foods. p. 140

Questions

- So many of the books I’ve covered so far this year re-iterate that we all are worthy of love and belonging. And, yet, so few of us have internalized this message. Why do you think that is?

- Fill in the blank from page 13.

- Where in your life do you allow yourself to be imperfect?

- Imagine community care – what does it look like to you?

- Would you say you live most of your life in your brain or your body? When was the last time you experienced joyful movement?

- Are there other realms of your life where you can apply Davis’ philosophies?

If you are struggling with care tasks, or feelings of shame, I strongly recommend reading Davis’ book. Next month, we’ll review Set Boundaries, Find Peace by Nedra Glover Tawwab, which – honestly – I thought I’d get more out of. Until then, surfs up!

- Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generationby Meredith Plummer

They Lied to Us

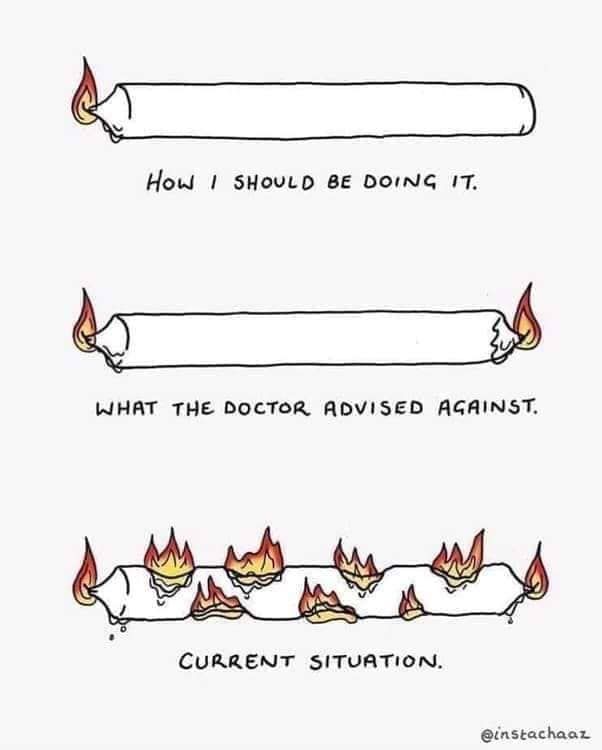

A meme from @instachaaz. When I was growing up, all the adults around me seemed to offer the same life advice, “Work hard, go to a good college, graduate with a ‘useful’ degree, and it will all work out.” Mixed in there was also some messaging, as subtle as it was, about finding “the one,” settling down, and having a family. It was a formula I was assured would bring me all my heart’s desires, and would not fail. And, so, being the trusting person that I am, I followed the plan. I worked hard to “overcome” my disability (there is no such thing, but that’s a story for another time); I attended one of Ohio’s top ranked public university; I graduated with high honors with a BS in Education; I settled down with my kind and loving partner; We started a family… and it didn’t all work out as promised.

Sound familiar? If so, then you might have grown up as a middle-class white Millennial too. In her book, Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation, Anne Helen Petersen explores this generational phenomenon, and how the messaging we’ve received over our lifetime has led Millennials to a constant state of Burnout. Here are some key quotes and questions I took away from Petersen’s book (p.s. please excuse the excess of quotes – this book really did speak to me)…

Quotes

- It’s not just the American Dream that’s broken, it’s America… that’s a deeply discombobulating realization, but it’s one that people who haven’t navigated our world with the privileges of whiteness, middle-class-ness, or citizenship have understood for some time. p. xvii

- Every day, we all have a list of things that need to get done, places where our mental energy must be allocated first. But that energy is finite, and when you keep trying to pretend that it isn’t – that’s when burnout arrives. p. xvii

- Increasingly – and increasingly among Millennials – burnout isn’t just a temporary affliction. It’s our contemporary condition. p. xx

- Millennials live with the reality that we’re going to work forever, die before we pay off our student loans, potentially bankrupt our children with our care, or get wiped out in a global apocalypse. p. xxii

- [Speaking of Boomers in the 70s] Members of the middle class were so freaked out by seeping economic instability that they started pulling the ladder up behind them. p. 15

- Surrounded by perceived threats and growing uncertainty, middle-class boomers doubled down on what they could try to control: their children. p. 20

- ‘Concerted Cultivation’ p. 25

- For some Millennials, helicopter parenting wasn’t an over-reaction to class anxiety. It was the appropriate, measured reaction to real, not perceived, threat, and systemic racism. p. 35

- Boomer parents were worried about all the things parents are always worried about. But they were also deeply anxious about creating, sustaining, or “passing down” middle-class status amidst a period of widespread downward mobility – priming a generation of children to work, no matter the cost, until they achieved it. p. 37

- Millennials became the first generation to fully conceptualize themselves as walking college resumes. p. 47

- There are so many reasons for Millennial burnout. But one of the hardest to acknowledge is the one Ann Faces down every day: that the thing you worked so hard for, the thing you sacrificed for and physically suffered for, isn’t happiness, or passion, or freedom… it’s just the same thing it always was, event when it gets dressed up in the fancy robes of the education gospel: more work. p. 65

- “Do what you love and you’ll

never work a day in your lifework super fucking hard all the time with no separation and no boundaries and also take everything extremely personally.” – Adam J. Kurtz p. 69 - [Speaking of the ‘Great Recession’] “Millennials got bodied in the downturn. [They] graduated into the wort job market in eighty years. That did not just mean a few years of high unemployment, or a couple of years living in their parents’ basements. It meant a full decade of lost wages.” – Annie Lowrey p. 77

- Amongst my peers, I’ve noticed a generalized “come to Jesus” moment regarding job requirements and aspirations: They no longer want their dream job – they just want a job that doesn’t underpay them, overwork them, and guilt them into not advocating for themselves. p. 88

- We were told that college would be the way to a middle-class job. That wasn’t true. We were told that passion would eventually lead to profit, or at least a sustainable job where we were valued. That also wasn’t true. p. 92

- Left to its own devices, capitalism is not benevolent. p. 113

- There’s a startling disconnect between the ostensible health of the economy and the mental and physical health of those who power it. p. 114

- We’ve conditioned ourselves to ignore every signal from the body saying “this is too much” and we call that conditioning “grit” or “hustle.” p. 128

- When we look back on the period following the Great Recession, it will be remembered not as a time of great innovation, but of great exploitation, when tech companies reached “unicorn” status (valued over $1 billion) on the acks of employees they refused to even deign to label, let alone respect, as such. p. 141

- Which underlines the current conundrum: shitty work conditions produce burnout, but burnout – and the resultant inability, either through lack of energy or lack of resources, to resist exploitation – helps keep work shitty. p. 147

- [Speaking about the rise in connectivity through smart devices] They make it increasingly impossible to do the things that actually ground us. They turn a run in the woods into an opportunity for self-optimization. p. 152

- That’s how social media robs us of the moments that could counterbalance our burnout. It distances us from actual experiences as we obsess over documenting them. It turns us into needless multitaskers… it erodes what used to be known as leisure time. And perhaps most damagingly it destroys opportunities for solitude. p. 164

- [Speaking of Instagram] And it’s become so intertwined with my performance of self that I fear there’s no self without it. That’s an exaggeration, maybe. But the prospect of relearning who I am – and who others are – remains daunting. I’m already exhausted, I tell themself. Where would I find the energy to do something that hard? p. 165

- Consuming news makes it feel like you’re doing something even if it’s just bearing witness. Of course, bearing witness takes a toll – especially when the news is structured to emotionally aggravate more than educate. p. 170

- Deep down, Millennials know the primary exacerbator of burnout isn’t really email, or Instagram, or a constant stream of news alerts. It’s the continuous failure to reach the impossible expectations we’ve set for ourselves. p. 177

- Part of our problem is that we work more. But the other problem is that the hours when we’re not technically working never feel free from optimization – either of the body, the mind, or one’s social status. p. 180

- Since 1970, there’d been a steady, year-after-year increase in the amount of work Americans performed, and a dramatic decrease in average leisure time. p. 185

- When people do find the time and mental space to cultivate a hobby, especially if you’re “good” at it, then pressure to monetize it begins to accumulate. p. 197

- Back in 2000, the book “Bowling Alone,” written by the political scientist Robert Putnam, argued that American participation in groups, clubs, and organizations – religious, cultural, or otherwise – had precipitously dropped, as had the “social cohesion” that sprang from regular participation in them. p. 199

- In “Palaces for the People,” Erik Klinenberg suggests that part of the decline in social ties is rooted in our preference for efficiency… But, part of the problem, too, is a decline in social infrastructure: the spaces, public and private, from libraries to supper clubs and synagogues, that made it easy to cultivate informal, nonmonetary ties. p. 200

- I’ve forgotten not just how to wait, but even how to let my mind wonder and play. p. 204

- That’s why the burnout condition is more than just addiction to work. It’s an alienation from the self, and from desire. p. 205

- Similar to the paradigm of overwork, [good parenting] equates exhaustion with skill, or aptitude, or devotion. The “best” parents are the ones who give until there’s nothing left of themselves. And, worst of all, there’s little evidence that actually makes kids lives better. p. 209

- Parenting burnout does not uniquely affect mothers. But because mothers continue to perform the vast majority of the labor in homes with a mother and a father, it affects mothers most. p. 209

- [Today’s mothers are] “free” to be pressured to be everything to everyone at all times, save herself. p. 210

- Between 1965 and 2003, men’s portion of unpaid family work rose from 20 percent to nearly 30 percent. But since 2003, that figure has remained stubbornly in place… women who work for pay outside the home still shoulder 65 percent of childcare responsibilities. p. 212

- Modern parenting has always in some way been about doubting your own competence. But never before has that doubt arrived with such force from so many vectors. p. 217

- ‘Competitive Martyrdom’ p. 221

- It’s the Millennial way: If the system is rigged against you, just try harder. Which helps explain one of the most curious stats of the last forty years: Women with jobs spend just as much time parenting as stay-at-home mothers died in the 1970s. p. 223

- ‘Role Overload’ p. 224

- It’s a particular sort of exhaustion to be poor. It’s exhausting to be stigmatized by society, to navigate social programs intended to help that mostly shame. A social worker once told me that he feels that American bureaucracy for aid is intentionally and endlessly tedious as a means to deter those who need it most. p. 232

- Some middle-class millennials grew up with packed schedules – but those pale in comparison to the way middle-class millennials now feel compelled to schedule their own children. p. 236

- Men still don’t value domestic labor, and men predominate our legislative bodies and the vast majority of our corporations. They don’t treat contemporary parenting – its cost, or the burnout that accompanies it – as a problem, let alone a crisis, because they cannot, or refuse to, empathize with it. p. 240

- You can’t fix parenting burnout by making time for Bible Study or journaling in the morning… or by learning how to fight like an adult… you can’t fix it with “self-care”… you can make yourself (temporarily) feel better, but the world will still feel broken. p. 242

- That’s an incredibly liberating thought: that what we’ve been taught is “just the way things are” doesn’t have to be. p. 251

Questions

- What messages did you receive in childhood about success and how to succeed?

- Which of these messages have served you well?

- Which of these messages are no longer based in reality?

- If you are a parent, what messages do you want to pass onto your children about success and how to succeed?

- What messages are you passing on to your children?

- Are you feeling burnt-out?

- If so, in what realm of your life is the burnout most prominent – work, technology, or parenting?

- Where is the pressure coming from – society or yourself?

- What would it take for you to stop the “hustle,” “disconnect,” and let your mind “wonder and play?”

- Where do you build social ties; where do you find community?

- If you are partnered, how is the domestic labor divided in your household?

- Is the division equal?

- Is the division equitable?

Thanks for bearing with me through all of that. Really, I can’t recommend this book enough. But, moving on, please note that I will not be posting in December. The holidays are always busy, and in an effort to combat my own burnout, I’ve decided to put down this blog for the month. I’ll return, however, in January with another mind blowing book; this one by notable psychologist and influencer K.C. Davis, How to Keep House While Drowning.